ELMs Case Study: Brigg, North Lincolnshire

Summary

- Family-run third generation business

- 6,500 sows across 17 sites

- Linked to arable business and feed mill

- Investing in upgrading facilities

- Introduced slurry treatment with Defra grant

- Feed advice critical to the business

- Not involved in stewardship

- Wary about ELMS

Background and farm description

This is a multi-site pig business owned and run by a farming family, run alongside their arable business and feed mill.

While each of these businesses is run as a separate profit centre, there is a high degree of synergy with many of the crops being supplied as feed to the group’s feed mill, and slurry from the pig enterprise being applied to the crops.

The director says: “We’re a family-run business farming pigs and operating our own feed mill. We also have a separate arable business. We are farming 6,500 sows and selling around 3,000 progeny to bacon every week.

“We have nine breeding farms spread across Lincolnshire within a fifty-mile radius of the office just outside Elsham. Most of those will finish their pigs on the same site but some will go to a separate site to be finished, and within the business, we have a total of 17 sites.”

Third generation

The farm director is the third generation of the family to be involved in the business. His grandfather was fattening pigs from the 1960s onwards. His father and uncle took on the business and from the early 1980s concentrated on breeding.

The feed mill was built in 1987 and the business has grown through acquisition until the mid-1990s when there was a slowdown in the market.

He says: “We have made a considerable investment in the last decade, but it is mainly re-investment in our existing sites to refurbish and upgrade them.

"Finishing houses have the shortest lifespan and that’s where much of the investment has gone but also in the farrowing houses. In addition, we have carried out a substantial project in slurry handling which was partly funded by a grant from Defra from 2018 to 2020 to reduce the pH.

“Most of the slurry goes to the arable business which is largely owned by the same shareholders as the pig business. The two businesses are closely aligned even though it is legally a separate entity.”

Arable business

The arable business is around 4400 hectares, mostly owned but with some land rented. At any one time, some 3,500 hectares are in production growing mainly wheat and barley which both go through the feed mill. In addition, they grow potatoes, sugar beet, vining peas and oilseed rape.

The director says: “The main thing which we have to buy in is soya, although we do buy some additional wheat and barley. Other materials we are putting into the mill include extracted rape meal, wheat feed from milling, and oil, particularly fish oil.”

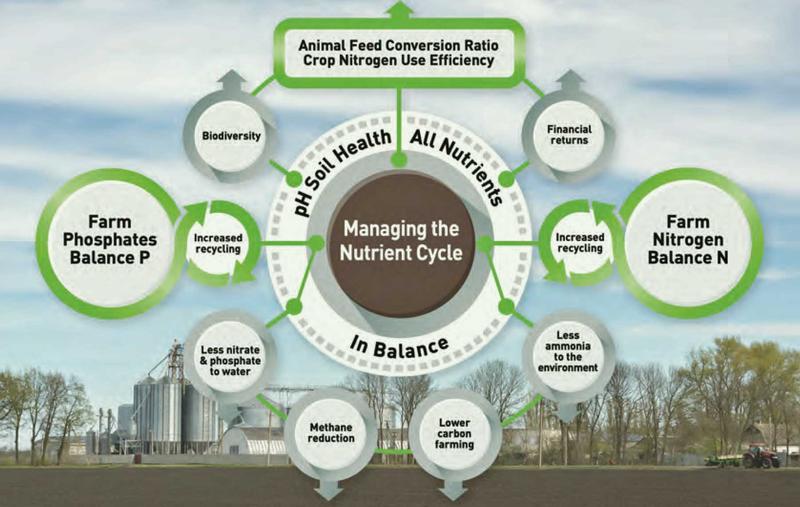

Support for industry led nutrient management campaign

A joint campaign has been launched designed to achieve ‘Farm Nutrient Balance’. The campaign is supported by a wide range of organisations including AHDB, AICC, BASIS, BGS, CLA, FACTS, FAR, LEAF, NFU and NIAB.

The campaign calls for improvements in three key areas:

- Farm Nutrient Balance

- Feed Conversion Ratio

- Nitrogen Use Efficiency

This case study is an excellent example of how these principles can be applied in the livestock sector.

Role of advisers and network

The key advisers to the business are a nutritionist and the company’s vet. The director says: “The adviser on the nutrition side and our vet, providing input on pig health, are the two crucial advisers to the business and they will often work together.”

Independent agronomy advice is provided to the arable business by a distributor company.

The nutritionist adviser says: “My role is very straightforward, every month I am given a list of prices for feed ingredients and it’s my job to ensure that the diet given to each pig and each stage of production is optimised for its cost and ensure that it delivers the nutrition for optimal growth.

“In the business, we have gilts, which are pre-pregnant sows, pregnant sows, and lactating sows. All of them have very different nutritional requirements, and then there are the piglets when they are weaned.

"Their nutritional needs change as they grow towards slaughter. I have to ensure they get the right nutrition within the Environmental Permit regulations, and also that the nutrients are being utilised and do not exceed maximum limits in the excreted manures.

“For me, the main ways in which my success is measured is live weight gain, feed conversion ratios and mortality. This focus works for the pigs, and ensures we meet our environmental obligations which fall out of feeding efficiently.”

Monthly performance review

The nutritionist reviews the performance of all the pigs within the business on a monthly basis. Unlike some businesses he works with that produce data on a six-monthly or quarterly basis, the farm business provides five-weekly data which enables him to make fine adjustments and optimise the diets for pigs at each stage of production.

Among other things, these changes have led to improvements over the past seven years with greater productivity making the business more sustainable.

The farm director says: “There are five key drivers which have increased the productivity of the herd. These are genetics, health, environment, training and nutrition. Our adviser has a key role in a number of these areas. Depending on the market, feed is up to two-thirds of our costs, so getting it right is critical to the sustainability of the business.”

As well as providing detailed data to the adviser, the farm is also able to trial different nutritional regimes and make comparisons across sites in order to improve their efficiency.

Although it has been difficult during the pandemic and bio-security means there is a limit to how many sites he can visit, the nutritionist tries to go to all of the farm enterprise sites on a regular basis to help him to assess their performances. Site managers can also contact him if they have problems and need his input.

The nutritionist says: “It’s good to see what’s actually happening on site and ensure that best practice is being followed. Also, I can talk to the staff and communicate the impact of excess protein or excess energy in the animals’ diet. I can’t do my job properly without getting out and seeing the farms and the pigs.”

Nutritionist is key

Talking about the nutritionist's role in the business, the farm director says: “We could not work without a good nutritionist. It’s a very specialist job and there are not many people who do his job nationwide. We don’t have the skills or experience within the business to design a pig ration.

"I have people who can buy the raw materials and possibly do the observational work on the farm, but formulating the ration is beyond us.

“His advice would be crucial to any long-term investment we make in feed systems as well. Although he wouldn’t be central to making decisions on genetics, he would also have an important role to play in the trials we carry out.”

Because of the work he does with other clients, the nutritionist is able to bring knowledge of a wider picture.

He says: “Overall I am responsible for around 40 to 50,000 sows in the UK, so there’s a lot of different genetics that I have experience designing diets for. If the farm decides to go down a particular route, I already have knowledge of feeding those pigs elsewhere.”

Environmental activity

While the farm has made a considerable investment in the infrastructure of the business over recent years, which will undoubtedly have increased its sustainability and reduced its wider environmental and carbon footprint, this was not at the time the primary motivation for the business.

The farm's director says: “Obviously by investing in the buildings and bringing them up-to-date they will have a lower environmental footprint. However, there is no financial return for improved sustainability and this investment was a commercial decision designed to save money and make an improved financial return into the business.

“All of the things we have done will have reduced the environmental impact per unit of production. The same applies to welfare. By investing in these buildings, we are improving the welfare of the animals - which is something we are very happy about - and also their productivity, but welfare is not the main driver.”

AD plant

One environmentally friendly initiative is an Anaerobic Digestion Plant built on land provided by the company. This has substantially reduced the cost of electricity to the feed mill and provides around 90 per cent of the power for the mill. Fuel for the AD plant is locally-produced maize but this is not grown on land farmed.

Another area that the company has been looking at is varying the pigs’ diets to produce slurry that makes more nitrogen available to the land. Ironically this would mean slightly less efficient nutrition but could make sense for the arable business given the high cost of fertiliser.

Overall, the feed nutritionist and the crop agronomist are looking for the best nutritional solutions and balance across the enterprises.

Attitude towards environmental stewardship and ELMS

Parts of the land used in the arable business has been in Countryside Stewardship. The company decided not to participate in the ELMS pilot, but will look carefully at the scheme once the details become clear.

The farm's director says: “The big problem there is that it is likely to be area-based. Because the land that we farm is grade one agricultural land and highly productive, we don’t have any areas that are not productive.

"Because the scheme is likely to work on a ‘per acre’ basis, it’s going to favour farmers who have more poor-quality land. We don’t want to be taking good quality land out of production.

“It very much depends on the details of the scheme when it is announced. There may be things that are applicable and if there are incentives rather than punishments we would welcome that approach.

"We don’t want to be a pariah for not participating, but equally, I don’t think it makes sense to take productive land out of production just to achieve a target. Better to use less or non-productive land for that purpose.

“If the scheme rewards activities, such as efficiencies in nutrient management (feeds, muck and fertilisers) we are already involved with, then we would look to be involved, but if we are being asked to change land use/introduce non-productive areas, such as planting trees there needs to be enough incentive on the table to do that.”

The nutritionist says: “I think that Defra have lost sight of the fact that animal welfare and sustainability have always been at the heart of what we do, and that will continue to be the case regardless of incentives.”

Slurry treatment

With the aid of a Countryside Productivity grant from Defra, the farm business has made a considerable investment in a treatment plant for slurry. This involves mild acidification of the slurry which lowers the pH and reduces the release of ammonia into the atmosphere.

The farm director says: “Normally we would keep finishing pigs in pens for 10 weeks and at the end, we would pull the plug and the slurry would drain, via a reception pit, into the slurry store. The pH of slurry is normally around 8 and the urea will break down into ammonia and it also releases some carbon dioxide.

"The ammonia becomes gas and, from a pig production point of view makes the atmosphere quite aggressive, and not good for the pigs.

“The slurry is pumped out and treated every day, and the solid element is separated, which helps when it comes to applying phosphate to the land, and then pumped back. The treatment reduces pH from 8 to 5.5, which means that the ammonia is far less likely to escape into the atmosphere and cuts ammonia emissions drastically – probably by 64% plus.

“Pumping the treated slurry back helps to reduce the pH of any newly produced slurry, keeping ammonia emissions low. Even when the slurry is applied to the land, the ammonia released is reduced, so there is a better utilisation of the nitrogen in the slurry.

“Capital cost is the biggest problem with this system and it is easier to install and run on a new-build compared to an existing facility. We could have put scrubbers in and reduced the ammonia emissions that way, but that wouldn’t have improved the atmosphere in the building and the pig performance.

“We are definitely seeing improvements in the atmosphere and we also believe it is improving pig performance but because there are other things going on it’s difficult to separate out the effects of the slurry treatment.”

Potential areas for ELMS

Many of the potential areas for ELMS relate to the company’s arable business or areas where the arable and pig business crossover such as slurry management.

- Soil management

- Nutrient management

- Livestock management – housing

- Livestock management – feeding and drinking water

- Slurry/manure management – storage and application